From slavery to freedom: the extraordinary story of C¨¢ndida Huelva

Born in 1845 in a Portuguese colony, she made it to Spain and became a local celebrity until her death at 110

The line between fact and fiction concerning C¨¢diz¡¯s last female victim of the slave trade is blurred, but what is known is that C¨¢ndida ¡®La Negra¡¯ was born into slavery in 1845 in the Portuguese colonial city of Luanda ¨C now Angola¡¯s capital ¨C and died a free woman 110 years later in Puerto de Santa Mar¨ªa, in C¨¢diz.

By then she had become a local legend in a city where nobody had seen a black person before, and it became common for children growing up between the 1920s and 1950s to be kissed goodnight with the cautionary words, ¡°Go to sleep now, or C¨¢ndida la Negra will get you.¡±

C¨¢ndida died in terrible poverty in 1951 with little known about her life

This tall woman who dressed in black and carried a basket filled with coal, knew what it was like to live both as a slave and as a free woman. She experienced two continents and two centuries, dying in terrible poverty in 1951 with little known about her life despite being a familiar figure in the community.

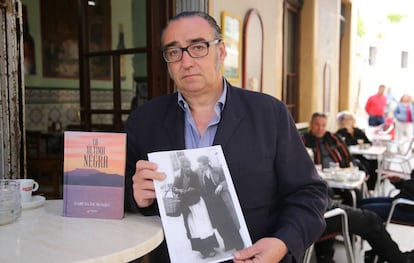

Still remembered as humble and friendly by C¨¢diz¡¯s oldest residents, C¨¢ndida Huelva is now the subject of a semi-fictional work by lawyer Joaqu¨ªn G. Romeu. Titled La ?ltima Negra (The Last Black Woman), it follows the course of her life, first as a slave in Luanda, and then as a free woman living on the fringes of a Spanish society dominated by bourgeois industrialists and hypocrisy.

The first person to try to unravel the mystery surrounding C¨¢ndida was the local historian Manuel Pacheco, who met her at the end of the 1940s when he was just a child. His curiosity had been stirred by the fact that the woman his mother had so often warned him about actually lived in the city. Many years later, in 2006, Pacheco¡¯s investigations into her life would result in an article called ¡°The Face of Slavery: the enthralling story of C¨¢ndida la Negra.¡±

The article explains how C¨¢ndida was washed up on the beaches of Puerto de Santa Mar¨ªa as a teenager in the mid 19th century, following a storm that wrecked the boat she was traveling on with her master. Pacheco claims an old peasant found her and took her home to his house on Lecher¨ªa Street 5 (now Cervantes Street), where she lived until the peasant¡¯s death.

A unique figure

Pacheco¡¯s reconstruction of these events was based on oral accounts from people who had spoken to C¨¢ndida many years earlier, before she decided to stop sharing her personal history with strangers. What can be taken as fact, however, is her date of birth, which municipal records show as May 2, 1845. These records also say that she was born in Luanda where a surname would indicate ethnic origin, master or place of origin. In C¨¢ndida¡¯s case, Pacheco traced her surname ¡®Huelva¡¯ to slave-owning families from Huelva.

The historian suggests she may have been in the process of being sold, as child-bearing women were highly valued in the slave trade. But Joaqu¨ªn G. Romeu points out that slavery on mainland Spain had been abolished in 1837, after which it was only tolerated in Spanish colonies such as Cuba and Puerto Rico as well as in Portuguese colonies. Hence, the novel depicts C¨¢ndida as a victim of the illegal slave trade that thrived between C¨¢diz and La Havana.

It¡¯s a story that could now almost make her seem like an activist Author Joaqu¨ªn G. Romeu

Not convinced by Pacheco¡¯s version of events, Romeu believes it was more likely that when the ship was offloading its merchandise in the port, C¨¢ndida managed to escape and was henceforth a free woman. Not that her freedom would have brought her much joy. After the Cadiz Slave Company stopped trading in the 18th century, it was hard to come across anyone like C¨¢ndida in the area and, as her legendary bogie woman status suggests, she would not have been easily accepted by the community.

After living with the old peasant, it would seem that C¨¢ndida got together with a Romani man who sold coal for a living. The couple, who had no children, would not make their match official until the 1940s when the Jesuits forced C¨¢ndida to be christened as C¨¢ndida Huelva Jim¨¦nez and to tie the knot. By that time, the locals had grown used to seeing her at the market with her coal basket, as she appears in the only photograph known to remain of her.

C¨¢ndida also did odd jobs for families in the city, and lived until the age of 110. It was then that she had an accident involving a coal heater and was rushed to San Juan de Dios Hospital, where she writhed in agony from burns for 20 days before finally breathing her last.

¡°It¡¯s a story that could now almost make her seem like an activist, though I doubt that she would have been aware of that,¡± says the author. ¡°She just wanted to survive and be able to eat every day, which, at that time, was quite an achievement in itself.¡±

English version by Heather Galloway.?

Tu suscripci¨®n se est¨¢ usando en otro dispositivo

?Quieres a?adir otro usuario a tu suscripci¨®n?

Si contin¨²as leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podr¨¢ leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripci¨®n se est¨¢ usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PA?S desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripci¨®n a la modalidad Premium, as¨ª podr¨¢s a?adir otro usuario. Cada uno acceder¨¢ con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitir¨¢ personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PA?S.

?Tienes una suscripci¨®n de empresa? Accede aqu¨ª para contratar m¨¢s cuentas.

En el caso de no saber qui¨¦n est¨¢ usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contrase?a aqu¨ª.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrar¨¢ en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que est¨¢ usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aqu¨ª los t¨¦rminos y condiciones de la suscripci¨®n digital.