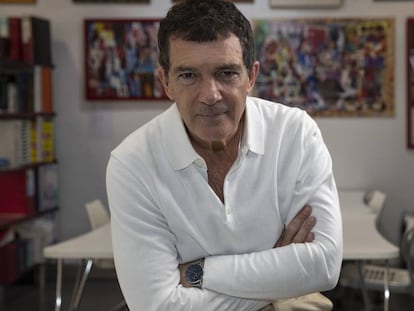

Is Spain¡¯s Antonio Banderas an ¡®actor of color¡¯?

Several US media outlets have been criticized for claiming that the Spaniard, who has been nominated for an Oscar this year, falls into this category

Even as this year¡¯s Academy Award nominations were being criticized earlier this week for their lack of diversity, a related social media controversy broke out when some US media outlets described Spanish actor Antonio Banderas, who is in the running for an Oscar, as ¡°an actor of color.¡±

Many people in Spain were surprised by the term used to describe this native of M¨¢laga. And in social media, some users called the publications ¡°racist¡± and ¡°yokel¡± for viewing the star of Pedro Almod¨®var¡¯s Pain and Glory as anything other than a white European. The online controversy about Banderas as a person of color extended to the other side of the Atlantic.

The online film industry publication Deadline has since deleted its tweet about ¡°two actors of color¡± ¨C Banderas and the African American actress Cynthia Erivo ¨C while Vanity Fair deleted a sentence saying that ¡°while Spaniards are not technically considered people of color, it should be noted¡± that Antonio Banderas has been nominated for his lead role in Pain and Glory.

There was a similar controversy in September of last year at the MTV awards, where the singer Rosal¨ªa, who hails from a small town in Barcelona province, was categorized as Latina, Hispanic and European.

Adapting the census

In the United States, ethnic labels have carried a political weight for decades, and they have been used to fight discrimination and increase the visibility of various communities. In the 1970s, the US Census included a ¡°Hispanic¡± category to group people from Spanish-speaking countries. Before that, Mexican-Americans had to describe themselves as white, but groups of activists fought to include a new category that would acknowledge their origins.

Race is a social construct that varies depending on where a person grows up and the country where they live

Clara Rodr¨ªguez, Fordham University

But the term Hispanic did not satisfy those who did not identify with the legacy of Spain¡¯s colonial past, and ¡°Latino¡± emerged, which also included indigenous people and Brazilians.

Clara Rodr¨ªguez, a sociologist who specializes in racial and ethnic categorization issues, says that the first thing she asks her students at Fordham University, in New York, is: ¡°What are you?¡±

¡°Race is a social construct that varies depending on where a person grows up and the country where they live. In Puerto Rico I am white, but in the United States, I am not,¡± she notes.

Asked whether Antonio Banderas could be considered a person of color, her answer is simple: ¡°Ask him. Ricky Martin is not dark-skinned, but he identifies as a person of color because of his Puerto Rican origins.¡±

The writer Ed Morales, author of Latinx: The New Force in American Politics and Culture, notes that language is also a very important racial determinant in the US. ¡°If a police officer arrests you and you have a strong Spanish accent, his perception about your race, independently of how you see yourself, could change,¡± he says in a telephone interview.

Morales adds that before World War II, no American would ever have considered Antonio Banderas to be a white man ¨C not him nor any other southern European. ¡°When they fought with us, the definition of white changed.¡±

A key tool to understand the United States¡¯ relationship to race and ethnicity is the US Census. The survey began in 1790 with just three options: free whites, other free persons, and slaves. The latest version, from 2010, makes a distinction between Hispanics, Latinos and people of Spanish origin; it also specifies Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans and other origins.

¡°Thirty years ago, the majority of people believed that each person¡¯s race was obvious, and that this was a genetic and biological issue. But now a lot more people feel that it¡¯s a social construct. And that¡¯s progress. Now we better understand the complex idea that race depends on the perception that we each have of ourselves,¡± explains Morales, who has contributed to The New York Times and The Washington Post.

Ram¨®n A. Guti¨¦rrez, who teaches history at Chicago University, says he is amused by the Banderas controversy. ¡°Some media used Banderas¡¯ photo as evidence that Hollywood is not racist, but the result was racism and exclusion,¡± he says.

Like most scholars on the matter, Guti¨¦rrez defends that race is subjective, and that, paraphrasing the African-American activist Malcolm X, ¡°racism is like a Cadillac, they bring out a new model every year.¡±

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripci¨®n se est¨¢ usando en otro dispositivo

?Quieres a?adir otro usuario a tu suscripci¨®n?

Si contin¨²as leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podr¨¢ leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripci¨®n se est¨¢ usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PA?S desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripci¨®n a la modalidad Premium, as¨ª podr¨¢s a?adir otro usuario. Cada uno acceder¨¢ con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitir¨¢ personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PA?S.

?Tienes una suscripci¨®n de empresa? Accede aqu¨ª para contratar m¨¢s cuentas.

En el caso de no saber qui¨¦n est¨¢ usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contrase?a aqu¨ª.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrar¨¢ en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que est¨¢ usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aqu¨ª los t¨¦rminos y condiciones de la suscripci¨®n digital.