Mercamadrid: Noahí»s other ark

Like a journey to another galaxy, this night trip to Mercamadrid has an element of science fiction about it. But the piles of fruit and vegetables and the tons of animal carcasses and fish that arrive at this immense wholesale food market are as real as life itself

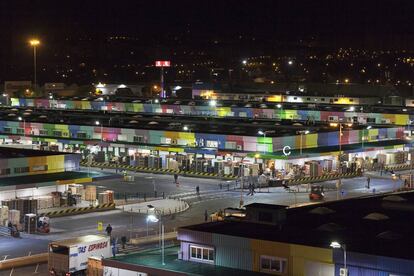

I was driving along Madridí»s M-40 ring road around 1am when the satnav ordered me to turn right onto a dark, lonely road along which I had the sensation of flying, rather than driving. And it suddenly seemed as though I was at the helm of a spaceship taking me to Mars, even though the brightly lit entrance with its line of toll booths had a huge sign announcing I had, in fact, arrived at Mercamadrid, the largest wholesale food market in Spain.

After having my credentials checked, I crossed to the other side and started to look around the streets of this strange planet that comes to life at night.

Immediately, I noticed that most of the vehicles on the site ĘC around 15,000 a day ĘC have more wheels than a caterpillar has legs. Ií»m talking about those kinds of wheels that that come up to a maní»s chest and support a cabin that looks like the head of a cyclopean insect with various pairs of eyes, which, in turn, is joined to the abdomen ĘC or trailer ĘC by a very slight mesothorax that is all but invisible, like the waist of a wasp.

These monstrous trucks chug up to the loading bay of one or another of the vast warehouses, reverse and disgorge products ranging from lobsters to calvesí» carcasses, eggplant to sea bass, rabbits to avocados, in inconceivable quantities.

Under a bright moon, the loading bays seethe with people and machines that carry out what seems at first to be a chaotic choreography, although on closer inspection is a precise dance, measured down to the last millimeter. Forklifts steered by experienced workers whirl around obstacles and miraculously avoid collision. They set down their containers inside the warehouse and scoot back to the truck like ants might go back and forth to their anthill. It brings to mind the inside of a drop of water seen under a microscope, in which a multitude of beings of different shapes and sizes are engaged in movement that seems to take them nowhere, yet constitutes an entire ecosystem.

The fish market, with its immense variety, is the second biggest in the world

If weí»re talking about the fish warehouse, however, the drop of water is some 400 meters long and 150 meters wide, and divided into lanes with traffic going both ways, forming streets lined by wholesale merchants who now start to display their goods so that when the neighborhood fishmongers arrive, they can choose the hake or the sea bass that they will offer their own customers.

The intruding journalist goes from one side of the warehouse to the other, armed with a pen and notebook in which he tries to capture the vibrant energy generated by the man dragging a sack of ice or by another one who is lugging a swordfish as tall as a teenager over his shoulder, or the man who is slicing open a tuna fish equal to him in size and weighing 200 kilos. He does so with the sharpest of knives on what looks like a surgeoní»s table set up in the middle of a combat zone, and extracts in a single gesture the entrails that have been wrapped in a cocoon of meat that stains the container red with organic waste ĘC waste that will be ground into flour for cosmetic products and animal feed.

This is the day-to-day of a huge bazaar populated by a multitude of species

Everything is done at lightning speed beneath the glare of the lamps that illuminate the warehouse. Outside, white birds are suddenly silhouetted against a night sky like spirits that have left their bodies but turn out to be seagulls: gulls so far from the sea that theyí»ve turned up on Mars.

What several hours ago looked like a puzzle that had accidentally been scattered on the floor, now appears more like a painting in which each product has its place. At one stall, thereí»s a collection of lobsters so dark they look like the obscure nooks in the sea rocks that harbored them; at another stall, thereí»s a family of red sea bream with eyes big and round with surprise. And at yet another, thereí»s a box of sturgeon with mysterious expressions and equally enigmatic-looking turbot; and then, too, we see plaice, dogfish, crab, sea bass and sea urchins. There are monk-fish with their breasts cut open like a legionnaireí»s shirt, and barnacles the size of a thumb, clams and squid, baby squid, halibut, cockles, oysters, Chilean hake, wild sea bass, Mediterranean shrimp, and Thai red prawns.

The fish are as colorful in their own way as the land-grown fruit and vegetables, coming in shades of red, blues, amber, whites, greys, yellows, oranges and, of course, blacks. Mercamadridí»s fish market is the biggest in the world after Tokyoí»s Tsukiji Market, though in Madrid you can find any type of fish under the sun. The trucks come from Spainí»s coastlines but also from Greece and Turkey, from Denmark and elsewhere in northern Europe. Some come from the nearby Adolfo SuĘórez-Barajas airport, with fish that have been flown in by plane.

Our senses bring us to a halt at a stall that was set up little more than two weeks ago and sells ready-made gourmet products ĘC a strange sight amid so much fresh produce. Juan Eugenio HernĘóndez runs it, offering hamburgers made from octopus, mussels and seaweed and cuttlefish with shrimp.

í░Weí»ve got roast eel from Holland here, crab claws and here, marine plankton,í▒ he explains.

í░Marine plankton?í▒

Passing the fruit warehouse, the air is noticeably warmer

í░Yes, ití»s used like saffron,í▒ he explains, showing us a collection of eggs that could be mistaken for jewels.

He goes on to show us the collection of mojamas (filleted salt-cured tuna) that are generally vacuum-packed, and red salmon and the cod steaks that come from Alaska as well as the Asian produce such as the soft-shelled crab popular in Japanese restaurants, which is very crispy once cooked.

í░This crab is caught just after it sheds its shell, which is why the new shell hasní»t become hard yet,í▒ he explains.

Not far from Juan Eugenioí»s stall, we stop to chat with ?scar Onaindʬa, 38, a second-generation merchant. He has three stalls, one that specializes in farmed golden sea bass, but also turbot, which looks good enough to eat raw. Then our attention is caught by a black fish weí»ve never seen whole before. Oscar picks it up to show us. Ití»s a sturgeon, the fish that lays the famous eggs we call caviar, and which also comes from a fish farm ĘC from the Aragonese Pyrenees to be exact ĘC and looks like nothing so much as a secret agent.

Ití»s incredible that so much death produces such an aura of life, and we leave the warehouse with the feeling that we are walking out on a party that is just getting started. The fact is we would have liked to stay until dawn to eat pigsí» ears and French fries at one of the local bars. But we also want to look around one of the six fruit and vegetable warehouses to see what the difference is between food from the sea and food from the land. Scarcely over the threshold, we are struck by the fact the air is warmer here, and the produce gives off a totally different smell that is impossible to define ĘC only an expert could separate the fragrance of one fruit from another.

Here, the logistics of the operation resemble the circulatory system of a human body

Meanwhile, the palette of colors is on a scale that makes it hard to take in, the tones being stronger than those of the fish. Initially, you are struck by the dominance of green in a myriad of shades, but then the shapes begin to absorb you, with some more masculine and others more feminine as well as those that appear to be representations of mammals in general. Whole mammals or simply their body parts ĘC in every bean we can see a kidney and in the beans from La Granja, we perceive lungs. The inside of walnuts reveal brains, the parsley looks like nerve endings and the ginger roots bear an uncanny resemblance to the digestive system. Inside the tomato, it is not hard to imagine the valves that separate the atria from the ventricles of the heart. And when it comes to the sweet potatoes, they are dead ringers for the pancreas, while the celery looks like muscles as they are presented to children in biology textbooks.

The passages here are lined with boxes and containers twice our height. Touch brings an infinite number of impressions. Just scraping the tips of your fingers along these walls, the sensation changes according to the fruit or vegetable they contain, from strawberries and zucchini, to oranges, peppers, kiwi, cooking apples, avocado, mango, banana, lemons, cassava and persimmon.

We move toward a huge stall laden with mouthwatering bunches of grapes. Selling them is FĘŽlix Palacios, a third-generation merchant from Alicante. í░I started with grapes from the VinalopĘ« Valley and then brought them from all over the world,í▒ he says. í░You have grapes here from Peru, Chile, Brazil, Italy, South Africaíş Look, these have no pips. A lot come like that now, although the pips are good because they help us to clean our colon.í▒

We walk between the boxes of grapes that gleam like diamonds. í░Have you noticed how beautiful they are?í▒ he says. í░Ií»ve got between eight and 10 varieties. The world of grapes is fascinating.í▒

He also tells us that the tastiest ones are those that doní»t last long, and that he would be prepared to talk to us for hours about it if it werení»t for the flood of shopkeepers who have started to come in.

í░How does the buying and selling work here?í▒ we ask before leaving him to it.

í░As we are working with perishables, everything is done quickly,í▒ he tells us. Then he adds with a satisfied smile: í░Can you tell that this is my world?í▒

You can.

It is nearly 6am when we decide to depart from this nocturnal city of provisions, fascinated by the way humans seem to imitate the way the body works in everything they do. The logistics are like the circulatory system and as such have a heart that pumps the product, and arteries through which it travels until it reaches the consumer who daily buys a tiny piece of what we have witnessed at their local market.

The visit to Mercamadrid has been like an adventure not unlike the 1960s science fiction odyssey Fantastic Voyage, starring Raquel Welch, in which two people, shrunk in size, are injected into a human body to see if they can remove a blood clot from an artery. We have been at the heart of where all the products are pumped out to be eaten by 12 million consumers. The adventure is over, and we make our way out into the cold early morning air.

A mega market

- Mercamadrid is one of the most important distribution centers for fresh produce in Europe.

- It belongs to the City of Madrid and the public company Mercasa.

- It occupies 222 hectares and houses 800 firms.

- In 2016, Mercamadrid sold 2.5 million tons of fresh produce.

- Around 20,000 people come here daily to buy and sell produce coming in from 50 countries and to be delivered to five continents.

- It provides food for 12 million consumers living within a 500-kilometer radius of its premises.

- Second- and third-generation merchants head a team of 8,000 workers from 30 different countries.

English version by Heather Galloway.